Manipulated Photographs, Manipulated Memories

Photo manipulation is nearly as old, if not as old, as photography itself. It has been used in state propaganda, to unify nations, for aesthetic and creative expression, to generate fear, and the list goes on and on.

As technology advances, altering photographic images has become quite easy. This begs the question: do the images we see convey accurate information? To be clear, I am not directing this question towards creative endeavors or other avenues by which photo manipulation is permissible. Rather, I’m talking about photographic information that is presented as absolute and authentic in a way that can have personal and political consequences (e.g., courtroom evidence, photo journalism).

I will discuss how direct manipulation of photographic images (beyond the scope of altering contrast, exposure, sharpness, etc.) can create false memories of events that never occurred. These manipulations change individuals’ memories and can alter how we understand history.

Inserting False Memories by Manipulating Photos

To study the phenomenon of false memories, a study was conducted to see if manipulated photos could be used to insert a false autobiographical memory into a participant’s personal history.

In this study, researchers invited pairs of adults and younger family members into the laboratory. For simplicity, I’ll use an example from one participant pair and call them father and son.

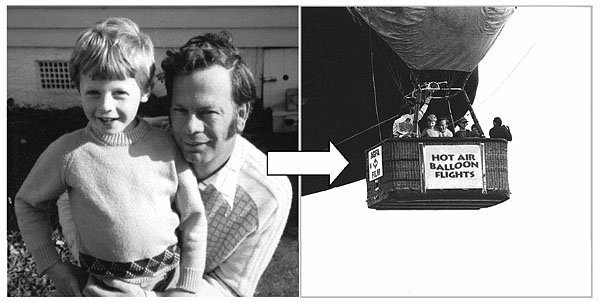

The father was aware that the purpose of the experiment was to insert a false memory, but the son was told that the study was to examine fond childhood memories. The son was presented with photos of real events that occurred during his childhood, but one of the photos was manipulated to make it seem like the father and son were in a hot air balloon (an event that never happened).

Sample doctored photographs by experimental condition

The experimenters instructed the son to tell them everything he could remember about each photo. When they reached the manipulated photo, the son could not recall what had happened. He was instructed to try his hardest and when he still could not remember, he was then was asked to imagine what could have happened.

Several days later, the father and son came back and went through the same exercise. On this second occasion, the son recalled specific details of the events in the manipulated photo, as if they had really happened. Here is an example of the first and last interview.

First Interview:

Subject: Mm… no, never actually thought I’d been in a hot air balloon, so there we go.

Interviewer: You can’t remember anything about this event?

Subject: Nah. Though it is me… no memory whatsoever.

Interviewer: If you want to take the next few minutes and concentrate on getting a memory back, something about

the event.

Subject: No, yeah I honestly… no I can’t. That’s really annoying.

Last Interview:

Interviewer: Same again, tell me everything you can recall about Event 3 without leaving anything out.

Subject: Um, just trying to work out how old my sister was; trying to get the exact… when it happened. But I’m still pretty certain it occurred when I was in form one (6th grade) at um the local school there… Um basically for $10 or something you could go up in a hot air balloon and go up about 20 odd meters… it would have been a Saturday and I think we went with, yeah, parents and, no it wasn’t, not my grandmother… not certain who any of the other people are there. Um, and I’m pretty certain that mum is down on the ground taking a photo.

It may seem surprising that a false memory was so easily created for this participant. Many of us tend to believe in the accuracy of our memories with great conviction, and we resist the idea that we could be so easily manipulated.

This participant, however, was far from an anomaly. Half of the participants in this study developed a false memory of the hot air balloon after they constructed a narrative about the manipulated photo.

In this occasion, a false memory of a hot air balloon ride probably had little impact on this child’s life. As I will discuss below, however, false memories can dramatically alter people’s lives.

Human Memory is Fragile

There are many ways in which errors in memory can occur. Let’s take an example presented by Jennifer Thompson and Ronald Cotton.

In 1984, Jennifer Thompson was a 22 year-old college student who was raped in her dorm room. Thompson reports purposefully studying her assailant’s face to later identify him and assist police investigation. When police detectives gave her photos of all the suspects, she studied their faces, and after several minutes, she narrowed her focus on a single photo – that of Ronald Cotton.

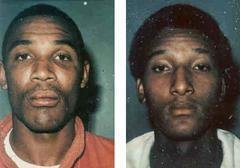

Later, during a police line up, she identified Cotton as the perpetrator, and the detectives told her that she identified the same man in the line up as in the photos. Cotton was sentenced to life in prison for this crime. The only problem was that Cotton was not guilty, and 11 years after his sentencing, he was exonerated by new technology that allowed for testing DNA evidence left at the scene of the crime. The real assailant was Bobby Poole.

Bobby Poole is on the left, Ronald Cotton on the right

What went wrong? First, Bobby Poole’s photo was not presented in the set of photos that police gave to Thompson, and she was not told that it was possible that the perpetrator might not be among those presented. Because Poole was not among the photos, she inadvertently chose the person who she believed most closely resembled her attacker (Poole is on the left, Cotton on the right).

Second, recognition memory is very fast, but Thompson took several minutes to study the photos. It is very likely that Thompson would have quickly recognized Poole, if his picture were included with the others.

The psychological research on human memory suggests that because Thompson was recalling what the rapist looked like while she was focusing on the suspect’s photographs, she most likely unintentionally combined features from her memory of Poole with Thompson’s features. Therefore, her memory seemed to become a composite of Poole and Cotton.

Third, the detective’s inadvertently reinforced Thompson’s choice of Cotton by stating she chose the same person in the line up as in the set of photos. When witnesses are subtly reinforced, their confidence in their choice and accuracy of their memory is much higher than if they are not reinforced at all.

Today, Thompson and Cotton travel around the country telling their story to bring attention to the inaccuracy of eyewitness testimony and how police investigators can limit errors in memory recall of victims and witnesses. Unfortunately, faulty testimony based on memory of the event is not uncommon, and there is current debate on how to overhaul how eyewitness testimony is used in the legal system.

Engineering History Through Photo Manipulation

Recent studies have shown that manipulating photos of important historical events changes the perception of historical memory.

In June of 1989, a university student led demonstration was held in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Nearly a million people took part in the demonstration to protest the Communist Party. On June 4th, the government responded by mobilizing the military, sending thousands of troops to suppress the demonstrators. The military response resulted in hundreds, if not thousands, of civilian deaths. During this time, several photographers captured a symbolic and powerful image of one student protester, who single handedly stopped a column of tanks sent to suppress the protestors.

Manipulated photo of “Tank Man”

False memory researcher Elizabeth Loftus conducted a study where she purposefully manipulated photos of the Tiananmen Square protests. In the real image of the event (above, left), a lone student blocked several tanks on their way to Tiananmen Square. The photo was manipulated to include a crowd of individuals on the sideline (above, right) as the student blocked the military tanks. Each participant saw one of the two photos. A significant number of participants from each group stated that they had seen the photo before, which provided evidence that the participants in the altered photo group believed that the picture was real.

At a later time point, participants from both groups, who stated that they knew about the Tiananmen Square protests and had seen the presented picture, were asked to recall the event. More specifically, they were asked use their memories of the event to determine how many individuals were part of the protest, and how many individuals were around the tanks. Those given the doctored photo said that they remembered the event as having many more people as compared to those who had seen the original photo.

For the altered-photo group, the act of recalling an event, along with false information (i.e., the manipulated photo), lead to a memory that was inaccurate and biased. This shows that by making a simple manipulation to the photo, people bias their memories to support the photo that they saw.

What is Real?

Photographs are known to assist in strengthening autobiographical memory. Further, they help us maintain important historical details as a society. Yet, at the same time, a manipulated photo can introduces false information into our personal and social histories.

Given the exponential growth of photographs taken and uploaded to social media sites each day, we should begin to explore how photography can be used in both helpful and harmful ways. How should we as individuals and as a society use photography to help maintain an accurate and precise history?

How do we know if our memories are our own or if they were manipulated? And, how can we identify when manipulated photos are negatively impacting our personal and collective memories?

Originally published on PetaPixel