Instagram and Anxiety of the Photographer – Part II

“The avant-garde of 1967 repeats the deeds and gestures of those in 1917. We are experiencing the end of the idea of modern art.” – Octavio Paz (1981), Nobel Laureate

In Part I of this series I discussed the aversion that artists of the modern art movement (~1850s-1950s) had concerning photography. I asserted that the rejection of photography by the modernists was rooted in their anxiety toward the rapid technological changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution. It was this aversion to technological integration with the arts that restricted new potential for art, alienated viewers, and eventually led to the downfall of the modernist’s power. As a result, painting, which was the established modernist form, began to weaken. At the same time, photography moved from the periphery of the art world towards its center. By the 1960s the transition from modernism to postmodernism began, and it was with the help of photography and its imbedded technological roots that helped to mobilize this evolution.

In Part II I’ll argue that mobile photography is ushering in an entirely new genre of art that is the culmination of the postmodernist art movement. I will elaborate on the development of postmodernism by tracing its lineage back to the radical Avant-Garde art movements of the 1910s and 1960s. Specifically, I’ll demonstrate how artists like Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol helped to create disruptive Avant-Garde techniques, in part, through the use of photography as a way to challenge the status quo. Furthermore, by linking the concepts of artists, social critics and academics during these periods, I’ll explain how photography has historically been used as an instrument to attack established art forms. My conclusion will show that during these windows of disruption there is immense social, political, and technological change that generates fear towards the unknown, that is, anxiety.

The Avant-Garde and Its Theoreticians: From 1915 to 1980

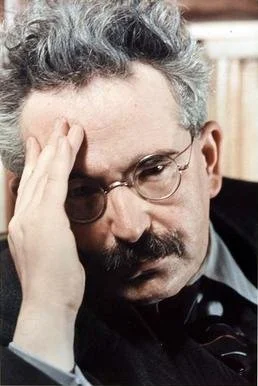

Postmodernism can be traced back, in part, to the radical and aggressive art movement that began nearly 100 years ago, referred to as the Avant-Garde. The Avant-Garde was short-lived, disruptive and consisted of different types of movements starting ~1915. One of the movements I’ll address is called Dada, a politically conscious group that formed in response to the atrocities of World War I. Dada attempted to annihilate modern art through the use of anti-art, which is the opposite of what art required at that time (e.g., to be handmade, to be aesthetically appealing, for the work itself to be more important than concepts related to it). For example, anti-art utilized machine made products, photography and collage as a way to fracture form, beauty and object, causing the viewer to reflect upon what art is. Though the Avant-Garde movement was brief, the impact became a central theme in the writings of social theorist and contemporary thinkers of the 1930s. One such thinker was Walter Benjamin, who greatly expanded the theoretical ideas of photography.

Walter Benjamin, 1939

Walter Benjamin saw the potential use for the Avant-Garde in socio-political change through the utilization of film and photography. Benjamin’s ideas coalesced during a time of great socio-political upheaval as fascist regimes were gaining power throughout Europe. Benjamin argued that the camera could be used by the masses to share their version of what was real, to disseminate information, and to resist state propaganda . For example, Mussolini and Hitler were adept at using visual symbols (i.e., propaganda) to direct their people’s attention away from immediate problems plaguing their nation such as class struggle, poverty, and unemployment. Propaganda was used to emotionally arouse nationalist pride and supported the idea of superiority toward other nations and people. Benjamin’s writings illustrate how photography, journalism, and documentation can be used to challenge political power, propaganda, and irrational nationalist fervor. Tragically, Benjamin’s life ended as a result of his attempt to escape Nazi occupied France, and with the destructive forces of World War II, many of his ideas fell by the wayside.

Artists, such as Andy Warhol (also see Robert Rauschenberg), started to revive the Avant-Garde during the 1960s when American modern art was at its peak. It was around this time that Walter Benjamin’s writings were more or less re-discovered. Benjamin’s ideas were used as an effective and popular way to interpret the renewal of the Avant-Garde movement. One of the most influential academics influenced by Benjamin was Rosalind Krauss, who started to adopt and define the term postmodern as a way to connect the Avant-Garde techniques and concepts of the 1910s to those of the 1960s. Krauss connected the Avant-Garde movements by using newly developed ideas in photography, linguistics, psychoanalysis and French social theory. Her writings show the near immediate change in photography’s relationship to the art world:

“The symptoms of a cultural awakening to this fact are everywhere: in the recent flurry of exhibitions; in the surge of collecting; in the rise of scholarly activity and in a growing sense of critical frustration about just what photography is. It is like the man who, finally accepting his doctor’s diagnosis, turns around and demands to know the precise nature of his illness.” – October (Art Journal) 1978

Defining Postmodernism – Marcel Duchamp and Conceptual Art

It’s difficult to define postmodernism because as an area of study it extends beyond the art world. However, we can revisit the Dada movement, specifically Marcel Duchamp, for a better read on postmodernist theory with regard to art. An important goal of postmodernism is to understand the modernism to postmodernism transition. The postmodernists carry out this goal by critiquing and deconstructing the events, works, and ideas of the modernist art movement. Additionally, it focuses on the theme of power by emphasizing the need to not put one theory above any other. Thus, postmodernism is a type of self-reflective analysis that favors (perhaps a little too much) political correctness. Marcel Duchamp shows this type of self-analysis and challenge to power exquisitely by putting a urinal in a museum.

Duchamp’s Fountain, Photographed by Alfred Stieglitz

In 1917 Duchamp entered an art piece called the Fountain to an exhibit organized by the Society of Independent Artists in New York City. Fountain was immediately rejected on the grounds that art was to be made by hand. Duchamp had purchased a urinal from a plumbing warehouse, wrote “R. Mutt 1917” on its side and proclaimed that it was art. In response to his rejection he wrote, in pseudonym (because he was well known and a founder of the society):

“Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – and created a new thought for that object.”

By re-contextualizing the urinal into the museum from a warehouse, Duchamp paved the road for conceptual art. It is the artist that dictates what art is, not those in power. If art is no longer required to be made by hand or to be beautiful, then what was art? This question illustrates why the Avant-Garde, particularly Duchamp and Dadaism, had such a great impact on the art world.

Yet, even the Dada became a commodity and their work was popularized and de-politicized. A popular view of postmodernism is that it’s simply a muted version of Dada, co-opted by art for profit. How then, did Dada go from radical to conventional? Some of this can be explained through the Avant-Garde movement re-established by Andy Warhol and Pop Art.

Pop Art as Consumer Avant-Garde

Just as photography started to become accepted into modern art in the 1950s and 60s, all the rules changed. Liz Wells, a contemporary thinker of photography theory, explains that the aesthetics and fine art prints that were once necessary for photographers to showcase in a museum were no longer essential.

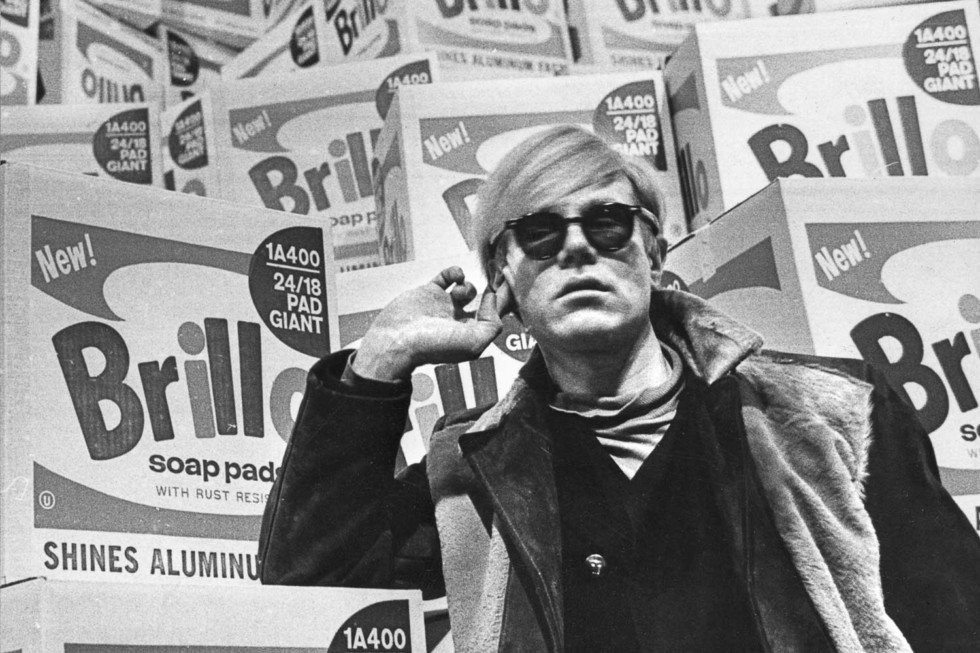

Andy Warhol Photo: Lasse Olsson/Pressens bild

The Avant-Garde artist of the 1960s and beyond took photography, and with it art, into a million different directions. The rules changed, largely because of Pop Art and Andy Warhol.

Warhol focused on commercialization and consumption in his work. Warhol’s first show, for example, was virtually invisible because his work was in a showcase for a high-end women’s department store, and it was not viewed as art; it was simply another commercial installation that promoted consumer behavior. Warhol was also fixated on producing art as if though he were a machine:

“Whatever I do, and do machine like, is because it’s what I want to do. I think it would be terrific if everybody was alike.” – Andy Warhol

His focus on mechanical technology was reminiscent of the Dada movement. For Duchamp it was a urinal, and for Warhol it was a set of Brillo Boxes; just like Duchamp, Andy Warhol turned an everyday object into art by re-contextualizing it. Warhol, like the Dadaists, looked toward popular and mass culture and worked to dissolve the barriers between the art world and social life.

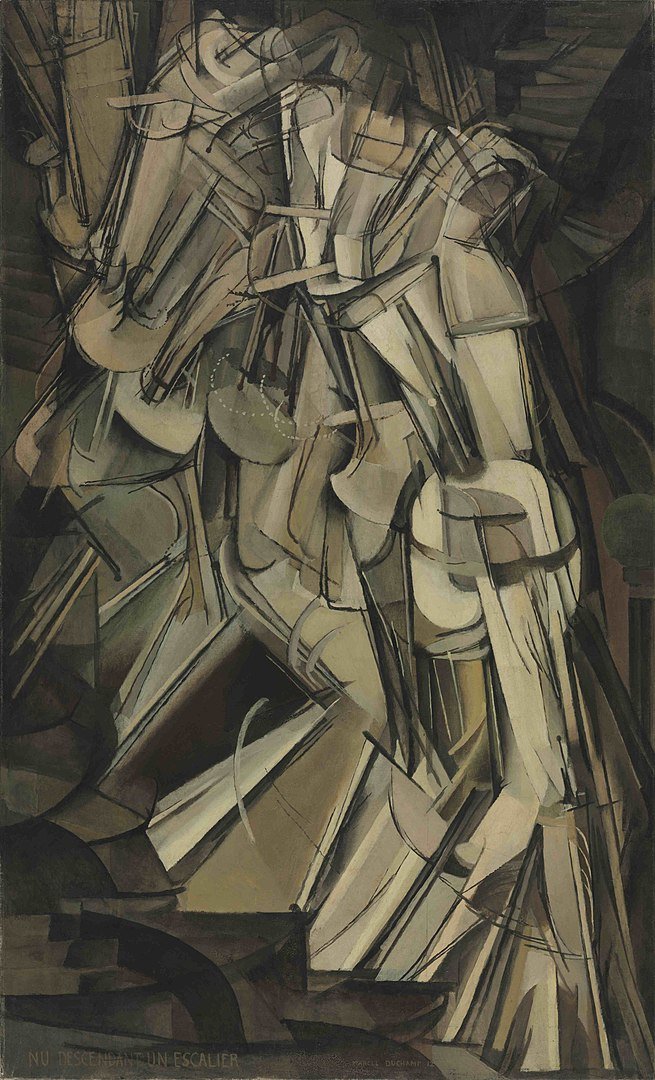

With regard to photography, both Duchamp and Warhol used or were directly motivated by photography in their own work. Duchamp’s Nude Descending Down Staircase, No. 2 was based off of Eadweard Muybridge’s motion pictures in the late 1800s. Additionally, the great modernist photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, photographed and published the image of Duchamp’s Fountain shown above. Warhol further catapulted photography as artwork. He appropriated images of Monroe and Elvis, obsessed over filming everything he possibly could and produced an incredible array of Polaroid images of popular icons in the media.

Duchamp’s Nude Descending Down Staircase, No. 2

During Warhol’s rise in popularity he made art commercial. Consumers increasingly demanded art, a market to understand art, and for art to be more accessible overall. Modern art’s grip began to weaken in the 1960s as the new Avant-Garde was changing all the rules, and it did so while acknowledging the Avant-Garde of the 1910s. However, the political nature of Dada was not the same as it was in Pop Art, which is one of the primary differences between the Avant-Garde of the 1910s and 1960s, the former being political and the latter focusing on consumer behavior. Postmodernist theory picks up on this difference and emphasizes the use of media technology to disseminate art as a consumer product, which fits perfectly into a little device called the iPhone.

Avant-Garde iPhoneography?

The works of Walter Benjamin, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol and Rosalind Krauss have greatly impacted the practice and conceptual framing of photography. These artists, social critics, and academics brought to view three related themes revealed by the Avant-Garde movements of the 1910s and 1960s: (1) subverting the institutions and concepts of their time; (2) utilizing technology to create, disseminate, and mass produce art; and (3) they occurred during a time of deep changes in the social and political structure. We see the same themes with mobile photography and the social media revolution.

The Avant-Garde movements of the 1910s, the 1960s, and the 2010s (via mobile photography) have not only changed photography but did so by further integrating technology with art, allowing photography to become unbound from its predecessor, unbound from space, and unbound from time as we once knew it. It is this fracturing of photography and art into all imaginable directions that generates anxiety about the future of photography (art by proxy) and creates a new generation of photographers unbound by the past. This opens up an entire generation to forms of thought that is nearly absent from the previous generation. But, we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves here. I’ll save these topics for the third and final article in this series.

Originally published on PetaPixel